For more than half a century, astronomers have been listening to space. They use powerful radio telescopes, hoping to pick up signals from civilizations in distant space. They call this project the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence, or SETI. The trouble is, they’ve never heard a single ping, beep or “howdy.” The number of aliens who want to talk to us seems to be exactly zilch.

So how can we get the conversation started? Scientists disagree.

They think Earthlings should start beaming signals out into the universe. Maybe it would improve our chances of hearing back from aliens if we let them know we’re friendly and want to chat.

This so-called “active SETI” would deliberately beam signals out in hopes of reaching space beings. Seth Shostak is an astronomer at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. He supports the idea. He also concedes that it is “extraordinarily controversial.”

Indeed, some scientists question the wisdom of advertising our presence. After all, maybe the aliens aren’t exactly what you’d call warm and cuddly. Do we really want to shout out to whomever will listen: “Here we are! Come invade our planet!”? At the very least, these scientists argue, people should discuss the idea and decide as a species whether we should try to actively put ourselves onto the radar screen of more technologically advanced beings.

“There are some people who think it’s dangerous, because you don’t know who’s out there,” Shostak says. “Maybe the aliens are just into yoga and poetry. But it could be that one percent of them are aggressive Klingons.”

Shostak doesn’t share these fears. But some people worry that if the aliens are not peaceable travelers, their response to even a friendly “hello” could be downright hostile. Some worry that instead of a friendly chat, those aliens might, as he puts it, “launch an attack and obliterate the Earth.”

David Brin doesn’t appreciate the Klingon jokes. He’s a scientist and science fiction writer. He also is one of those people who argues that Earthlings should proceed with caution. It’s not a matter of being afraid of some alien invasion, he says. “I know how unlikely those scenarios may be.” Instead, he thinks of active SETI almost like a potential environmental hazard.

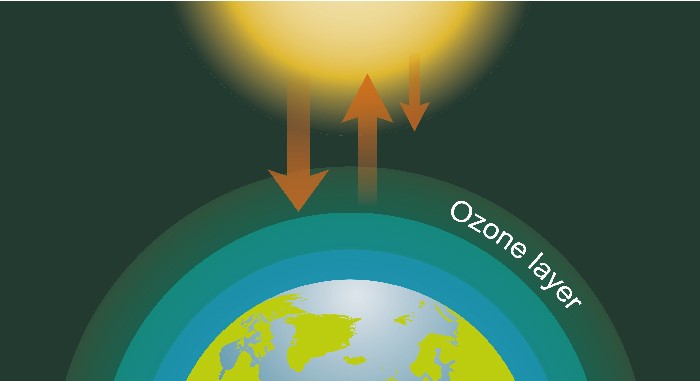

Broadcasting powerful signals would change the nature of our planet. It would make Earth more observable from space. Other projects must go through an environmental review, he says, and this should too. “What’s so hard about that to understand?”

As an astrobiologist, David Grinspoon studies the possibilities of life throughout the universe. He works for the Planetary Science Institute in Washington, D.C. Whatever Earthlings do, Grinspoon thinks it’s important for them to decide as a group.

“The more I think about it,” he explains, “the more it seems almost anti-human to say, ‘I’m just going to be the ambassador for the whole human race and start broadcasting to aliens on my own.’”

Alien life is likely, many scientists suspect

Inviting contact with space aliens might sound like the plot of one of Brin’s sci-fi novels. Yet plenty of researchers are taking this idea quite seriously. Even though we haven’t found extraterrestrials yet, many scientists believe that it’s quite likely that life exists on other worlds.

For one thing, science recently has shown that planets are much more common than astronomers had once thought. There are probably billions of them in the universe.

Biology also has turned up plenty of life on Earth that can survive and thrive in extreme environments — conditions that once were thought uninhabitable. These include places that are very hot, very cold, very dry or even bathed in acid.

“Everything we’ve learned about other planets and the diversity of life on Earth points us in the direction of believing there is abundant life elsewhere in the universe,” argues Grinspoon.

What’s more, even if life truly needed many of the same conditions found on our world, planets have been turning up that may host Earth-like temperatures, atmospheres — and perhaps even water. Such worlds exist in what’s known as “Goldilocks” zones. These are not too hot or too cold — but just right to sustain liquid water somewhere.

Whatever such alien life might be like — even if most of those organisms are just algae or worms — some would likely be intelligent, Grinspoon suspects. “It’s not just a fantasy that someone might pick up a signal if we broadcast it,” he says. “It’s my belief that there probably are creatures out there. And some of them probably have much more advanced technology than we do.”

So how would people try to contact other worlds? Scientists have a few ideas. Like a message in a bottle, people could put something into a capsule and shoot it into space. Or scientists could flash lights at the aliens, training the beams of super-powerful lasers at nearby star systems. Think of it like Boy Scouts waving their flashlights at girls who might be camping on the other side of a lake. Researchers would send radio broadcasts out across the vast expanses of space.

Douglas Vakoch is president of METI International in San Francisco, Calif. (METI stands for Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence.) In addition to other ideas for sending out signals, he recommends beaming radio messages at other stars with huge radio telescopes, like the Arecibo (Air-eh-SEE-boh) observatory in Puerto Rico.

Right now, Arecibo uses radar to probe our solar system. The telescope sends out a pulse of radio waves. How long it takes those signals to bounce off things, such as asteroids, tells us how far away those things are. Under Vakoch’s plan, the telescope would send out those same radar pulses. But he’d aim them at nearby star systems. If all went well, intelligent aliens would notice those radio tweets and answer our “beep” with a “boop.”

“Maybe some civilizations out there are doing what we’re doing,” Vakoch says. “They’re listening, but they’re not transmitting.” If they are, “we just wouldn’t discover them,” he notes. Active SETI, he explains, “is an attempt to let any civilization out there know not only that we’re here, but also that we’re interested in making contact.”

So why do we even want to talk to aliens? The search for extraterrestrial intelligence — or ETI — is part of humanity’s larger quest to explore the universe, and understand the nature of life, Vakoch says. “Perhaps more importantly, it holds a mirror up to ourselves.”

Throughout human history, any time civilizations have met, they have exchanged ideas, knowledge and technology. Meeting a more advanced culture could give our species a new perspective about life on Earth, says Vakoch. It might also show us new tools to solve Earthly problems, he adds.

Brin sees it a bit differently: “It’s worth bearing in mind that every time human civilizations that didn’t know about each other came into contact, there was pain.” Think about what happened to Native Americans or Africans when European explorers arrived on the scene, he says. Europeans coming to the “New World” brought along never-before-seen diseases. And their advanced technology, such as guns and metal, led to the destruction of the Native Americans’ way of life.

That’s one reason Brin thinks scientists and government leaders should not act too quickly. He advises that they think and talk it over before deciding what to do next. If we do contact aliens, studying our own history might give us ideas about ways to keep our interactions peaceful.

“Why did some contact situations [in history] go better than others?” Brin asks. “It turns out, there were some commonalities in the ones that were less painful. This should be something we study, not something we avoid.”

E.T. may already know about us

It’s probably too late to hide from advanced space civilizations, many scientists observe. Supporters of active SETI point out that FM radio and television signals both emit a high enough frequency that they could be picked up in space. Then there are all of those signals flying around between satellites, and those powerful radar pings from telescopes like Arecibo.

While people debate the issue, maybe the aliens are already watching our TV shows and listening to our music, says Philip Lubin. He’s a physicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “When someone says we shouldn’t transmit,” he notes, “you kind of have to say, ‘Okay, what planet do you live on?’ Because we’ve been transmitting for 100 years.”

Active SETI would take those transmissions to the next level. It would beam out more powerful signals, focusing them on the closest star systems. “The real question,” Lubin asks, “is should we transmit with the intention of being understood?”

Any civilization so advanced that it could visit Earth would already have the technology to pick up our signals, Vakoch agrees. So it would likely already know we’re here. In that case, he cautions: Maybe it’s in the best interest of the people of Earth to offer a peaceable greeting before those aliens pay us a visit. “There’s the idea that doing something is more dangerous than doing nothing,” Vakoch says. “But maybe it’s more dangerous not to say anything.”

He doesn’t want to wait to start active SETI. He does, however, agree that society should talk openly about the search for extraterrestrial life — and decide what to do if aliens respond. Most scientists have agreed to the “Protocols for an ETI Signal Detection.” This is a plan for what to do if aliens make contact with us. (Step one: Tell other scientists so they can confirm the discovery.) But Vakoch would like to see those policies debated and agreed to by the United Nations.

He concedes, though, “So far, we haven’t convinced [U.N. officials] that this should be at the top of their list.”

Grinspoon does think we should debate the issue before we broadcast messages into space. But it’s not because he’s afraid of ET. Discussing the welfare and future of our planet “is the kind of thing we humans need to get better at,” he says. In fact, the biggest threat to human civilization isn’t alien invasion, he argues. It’s things like climate change, war and pollution.

The only solution to those problems is to learn how to think and act not as different races and countries, but as one species, he says. “It’s actually more important to try to have a conversation with our fellow human beings than it is to have a conversation with aliens,” he says. “That is our survival challenge.”

Ever been to a party and wondered why no one was talking to you? That’s kind of how SETI scientists feel — but on a cosmic level.