It’s a question that then-MIT grad student Katie Bouman grappled with in an interview with the university’s news office back in June 2016.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) post-doctoral student Katie Bouman, who isn’t an astronomer, amazingly played a vital role in taking the first-ever photograph of a black hole.

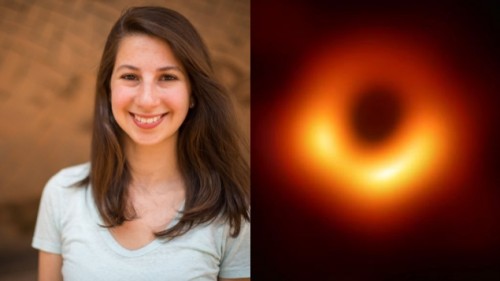

That historic first photo of a black hole was released to the public on Wednesday after years of work on an international project called Event Horizon Telescope.

Katie Bouman, a computer scientist, took the lead on creating the algorithm that made it possible to take the photo 55 million light-years away from Earth.

According to the Event Horizon Telescope website, "This long-sought image provides the strongest evidence to date for the existence of supermassive black holes and opens a new window onto the study of black holes, their event horizons, and gravity." In layman’s terms, this could change everything about how we think about the universe.

Three years ago MIT grad student led the creation of a new algorithm to produce the first-ever image of a black hole.

The snap, which has only been available to the public eye for a few hours, was taken using a worldwide network of powerful telescopes back in 2017.

The image of the black hole was taken in a galaxy known as M87, where, for 16 years, astronomers observed stars rotating in an orbit.

Scientists observing the stars determined that they were rotating around a supermassive black hole, and it is that black hole the whole world is now getting a glimpse of, in large thanks to Bouman’s contributions.

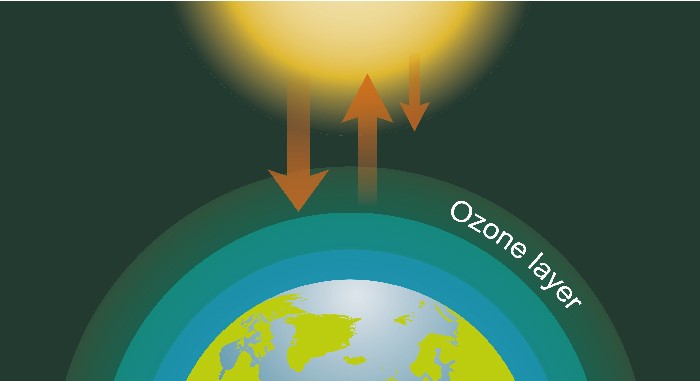

Unlike the common belief and despite the images advertised all the time on science TV channels the portrait of a black hole was never made by astronomers so far."A black hole is very, very far away and very compact," Bouman told MIT News. She compared taking a photo of a black hole in the Milky Way galaxy to photographing a grapefruit on the moon using a radio telescope.

"To image something this small means that we would need a telescope with a 10,000-kilometre diameter, which is not practical because the diameter of the Earth is not even 13,000 kilometers."

A few months later, Bouman gave a TED Talk in which she discussed how she and other members of the Event Horizon Telescope project — a team comprising what she described as "a melting pot of astronomers, physicists, mathematicians and engineers" — were working to use complex algorithms and data obtained from a global network of telescopes to try and stitch together

"You might be surprised to know that we may be seeing our first picture of a black hole in the next couple of years," she told the audience.

Sure enough, less than two and a half years after the TED Talk, the first ever photo of a black hole was revealed by scientists, with Bouman’s role in the project being hailed as a success story for young women in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics).

Bouman, now 29, wrote one of the imaging algorithms that helped piece together the photo by filling in the gaps in imaging data obtained from the telescopes.The image was obtained using data collected in April 2017 from eight radio telescopes in six locations — Arizona, Hawaii, Mexico, Chile, Spain and Antarctica.The team’s observations strongly validated the theory of general relativity proposed in 1915 by Albert Einstein to explain the laws of gravity and their relation to other natural forces.

"The image has this exquisite beauty in its simplicity," said astrophysicist Michael Johnson, the project’s imaging coordinator.

"It is just a fundamental statement about nature. It’s a really moving demonstration of just what humanity is capable of."

Junior researchers like Bouman made a crucial contribution to the project, senior MIT researcher Vincent Fish told CNN.

"One of the insights Katie brought to our imaging group is that there are natural images," Fish said.

"Just think about the photos you take with your camera phone — they have certain properties. … If you know what one pixel is, you have a good guess as to what the pixel is next to it."

How do you take a photograph of something that’s located 54 million light years away, has a mass 6.5 billion times that of our sun and doesn’t allow any light to escape?