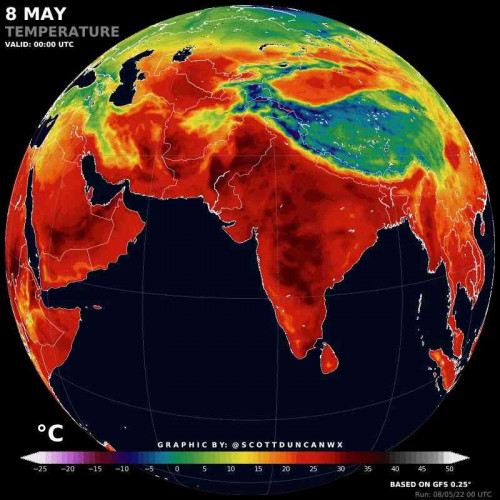

At this stage, even if we can limit global warming to 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, new estimates suggest the tropics and subtropics, including India, the Arabian peninsula and sub-Saharan Africa, will experience dangerously hot temperatures most days of the year by 2100.

The mid-latitudes of the world, meanwhile, will experience intense heat waves each year at least. In the United States city of Chicago, for instance, researchers predict a 16-fold increase in dangerous heat waves by the end of the century.

The chances of us avoiding that fate? About 0.1 percent, in terms of the projected probability of us limiting warming to below 1.5 °C above pre-industrial temperatures. In all probability, researchers say the world will have exceeded 2 °C of warming by 2050.

In this case, researchers say "extremely dangerous heat stress will be a regular feature of the climate in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Arabian peninsula, and much of the Indian subcontinent".

Unless the world can work together to implement rapid and widespread adaptation measures, there will likely be many deaths. But every bit we can reduce temperatures by still matters, because every fraction of a degree of less heat will save lives.

Recent estimates suggest global warming is already responsible for one in three heat-related deaths globally.

Based on these rates, other studies predict humans will die in record numbers in the coming decades as climate change tightens its grip on our planet.

How humans cope with heat stress, however, is complicated by other factors, like humidity. The current estimates are based on a metric known as the Heat Index, which only takes into account relative humidity up to certain temperatures.

This is the traditional measurement used by researchers to measure heat stress, and yet recent studies have found the human body might not be able to cope with as much heat and humidity as this index indicates.

As it stands, 93 °C (200 °F) on the Heat Index is considered the ceiling of what is survivable.

But at 100 percent humidity, new research suggests even young and healthy people may not live past 31 °C.

Nevertheless, on the traditional Heat Index, temperatures are considered dangerous when they exceed 40 °C (103°F) and extremely dangerous when they exceed 51 °C.

These are the thresholds the current study used to predict habitability in the future, and there's a good chance they are an underestimation of what is to come.

Even by this measure, however, humanity's prospects look dire.

Between 1979 to 1998, the dangerous Heat Index threshold was exceeded in the tropics and subtropics on 15 percent of the days each year.

During this time, it was rare for temperatures to become extremely dangerous as per the Heat Index.

Sadly, the same can't be said of today, and the problem is only getting worse.

By 2050, in tropical regions, the dangerous Heat Index could be exceeded on 50 percent of the days each year. By 2100, it could be exceeded on most days.

What's more, about 25 percent of those days could be so hot, they could exceed extremely dangerous thresholds.

"It is likely that, without major emissions reductions, large portions of the global tropics and subtropics would experience Heat Index levels higher than considered 'dangerous' for a majority of the year by the end of the century," the authors write.

"Without adaptation measures, this would greatly increase the incidence of heat-related illnesses and reduce outdoor working capacity in many regions where subsistence farming is important."

The health and societal consequences would no doubt be profound.

The world is heating up, and it's threatening habitability in many regions around the equator.