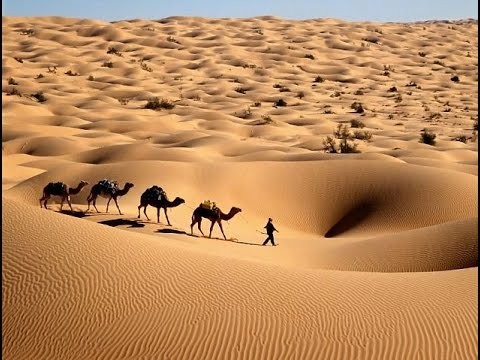

The Sahara, the largest desert in the world, has grown in size by around 10 percent since 1920.

Scientists say climate change is one of the most likely reasons why the sands are shifting into new regions.

What's more, this expansion of dry and arid landscapes might not be restricted to the Sahara either, based on variations in weather patterns and rising temperatures across the globe.

It's another sobering reminder of the consequences of a warmer world.

"Our results are specific to the Sahara, but they likely have implications for the world's other deserts," says senior author of the study Sumant Nigam from the University of Maryland (UMD).

The team found most variation in the northern and southern borders of the Sahara desert, and also examined conditions in the Sahel region, the transitional zone connecting the southern Sahara to the Sudanian Savanna.

"Many previous studies have documented trends in rainfall in the Sahara and Sahel," says one of the researchers, Natalie Thomas.

"But our paper is unique, in that we use these trends to infer changes in the desert expanse on the century timescale."

Digging into records going as far back as 1920, the researchers looked at average annual rainfall as a definition of what a desert actually is – in this case, less than 150 millimetres (5.9 inches) of rain per year.

Based on annual rather than seasonal trends, the Sahara stretched out by 10 percent over the course of 1920-2013, the researchers report. In the summer months, the expansion was as much as 16 percent.

Lake Chad, in the Sahel region, serves as a useful indicator of changing conditions along the border of the Sahara in the new study.

"The Chad Basin falls in the region where the Sahara has crept southward," says Nigam. "And the lake is drying out."

"It's a very visible footprint of reduced rainfall not just locally, but across the whole region. It's an integrator of declining water arrivals in the expansive Chad Basin."

A series of complex climate cycles affect conditions in the Sahara, including the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO).

Considering the AMO runs on a 50 to 70 year cycle, long-term studies like this one are crucial in understanding how our planet is changing.

However, the researchers think human-influenced climate change is affecting this desert creep as well, and that it could be happening elsewhere in the world.

Importantly, these shifts have a direct effect how much of our planet is habitable.

"Deserts generally form in the subtropics because of the Hadley circulation, through which air rises at the equator and descends in the subtropics," says Nigam.

"Climate change is likely to widen the Hadley circulation, causing northward advance of the subtropical deserts. The southward creep of the Sahara however suggests that additional mechanisms are at work as well, including climate cycles such as the AMO."

After factoring out the influences of the AMO and PDO, the researchers estimate around one third of the Sahara's expansion is down to climate change caused by human activity. That has implications for those who live in the Sahara as well as the wider world.

The planet's population continues to grow, which means we need more land to farm crops on, not less.

Now the researchers want to see studies looking at a wider selection of data over a longer period of time to get a more exact picture of what's happening.

"With this study, our priority was to document the long-term trends in rainfall and temperature in the Sahara," says Thomas.

"Our next step will be to look at what is driving these trends, for the Sahara and elsewhere."